By Gary Symons

TLL Editor in Chief

A CNN report argues companies are reducing the numbers of products they sell, in a trend with important ramifications for the licensing industry.

The report, which you can read AT THIS LINK, notes that companies like Hormel, Levi’s, Starbucks, Under Armour, Dollar General, Five Below, Hasbro, and Hain Celestial have begun a large scale reduction or trimming out of their product lines. The trend is meant to weed out less profitable product lines and focus on the brands that are bringing in the bulk of the profits.

From a licensing perspective, that also means it could be far more difficult to persuade some companies to launch a new line based on a licensing deal, at a time when they are actively reducing the number of SKUs they offer. The trend is being seen in fashion, food and beverage, toy and game, as well as at retail.

The CNN report provides the example of Hormel, saying, “Pepperoni was getting out of hand at Hormel. The food giant last year was selling 71 different versions of its Hormel Pepperoni brand. There was diced pepperoni. Turkey pepperoni. Mini-slices of turkey pepperoni. Pepperoni sticks. Pepperoni with 50% less sodium. Pepperoni with 25% less fat. Thick-sliced pepperoni. The list goes on.”

The problem was that several of those brands were not generating a lot of profits. In fact, Hormel found that 80% of its profit comes from a small number of products, including Hormel Bacon and Fire-Braised meats, while the rest of its tens of thousands of food items tend to actually drive up overall costs, while they “sit untouched in warehouses and on shelves for long periods.”

As a result, Hormel is on a campaign to rationalize its entire product line by removing, consolidating or repackaging roughly one-quarter of its items. The company says it will prune away the unprofitable items across dozens of brands, including Spam, Applegate and Jennie-O.

In that sense, Hormel seems to be following the ’80-20′ rule, removing the lower profit items and reinvesting in those with higher profit margins and popularity with the goal of removing “production complexity.”

“That’s just one example of companies eliminating an endless assortment of products to boost profit. For consumers, it means that they now have fewer choices for everything from sneakers to toys to coffee,” said the report by Nathaniel Meyersohn. “It’s a reversal of years of companies trying to give customers unlimited choices and shelves getting more and more cluttered with dozens of variations of the same item.”

So, what’s behind the trend?

That goes back to the beginning of the pandemic, which continues to influence consumer buying habits, as well as corporate production decisions.

Historically, brands have wanted to produce more products and thus take over more shelf space at stores, not to mention reacting to the latest consumer trends. During the beginning of the pandemic in 2020, customer demand skyrocketed and global supply chains ground to a halt. Companies sped up production lines for their primary, top-selling items and ruthlessly pared down their niche offerings, a strategy known as “SKU rationalization.”

Historically, brands have wanted to produce more products and thus take over more shelf space at stores, not to mention reacting to the latest consumer trends. During the beginning of the pandemic in 2020, customer demand skyrocketed and global supply chains ground to a halt. Companies sped up production lines for their primary, top-selling items and ruthlessly pared down their niche offerings, a strategy known as “SKU rationalization.”

After the pandemic, inflation began to take hold, due to the hangover of broken supply lines, the inflationary effect of governments pouring money into the economy to avoid recession, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, with both those countries being major exporters of food.

With food prices increasing some 26% in the US since 2020, companies are prudently thinning the herd of products they wrangle to the markets, simply because their sales volumes have dropped.

According to CNN, which interviewed executives from multiple companies, the same trend is happening in most of the other consumer categories.

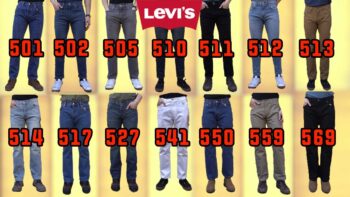

Levi’s cut 15% of clothing items across its portfolio, Hasbro has cut around half of its products, and Dollar General has taken roughly 10% of its products off the shelves. “We may have five or six different variants of mayonnaise on the shelf today. We can easily drop one or two of those. The consumer is not going to know the difference,” Dollar General CEO Todd Vasos said last year in an earnings call.

In cutting various toy and game products, Hasbro noted that the products they cut from their portfolio only accounted for two per cent of its profits. Hasbro’s CFO Gina Goetter pointed out many of those products were “duplicative and unprofitable, clogging the network and creating cost for us and our retailers.”

The issue for the licensing industry is that, with major companies cutting back on the number of products they offer, it becomes more difficult to convince their management to take on a new product, unless there is compelling evidence that product will produce significant profits in a reasonably short time.

Has your company encountered this trend? Have you witnessed changes in the way companies are addressing a pitch for a new and licensed product line? If so, tell us your story by sending an email to the editor, gary@thelicensingletter.com.

Surf Brand Hurley Partners With Drumming Legend Travis Barker