TLL Editor in Chief

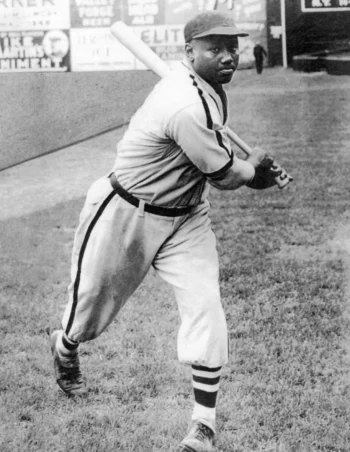

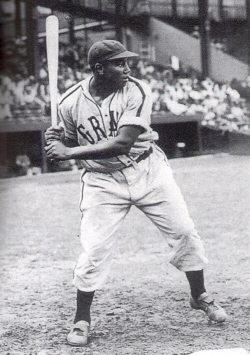

Major League Baseball is now including the player stats from the Negro Leagues, meaning players like the legendary Josh Gibson will finally be recognized for their incredible skill and accomplishments.

And now the MLB has recognized the players of the Negro Leagues, it’s certainly time for the licensing industry to do the same, both because it’s good business, but also because it will help correct an historical injustice.

The news blew up in headlines around the world, partly because the MLB has now recognized that Gibson is baseball’s all-time batting leader, with his career .372 average beating out Ty Cobb’s lifetime average of .367.

“Josh Gibson would have hit home runs in any league, in any era, had he been given the opportunity to do so,” Negro Leagues Baseball Museum president Bob Kendrick said earlier this year in a video produced in conjunction with MLB.

Gibson also holds the all-time record for the highest batting average for a single season, with his .466 record in 1943 playing for the Homestead Grays, beating out Hugh Duffy’s .440 average in 1894. He similarly beat out Barry Bonds to become the single season leader in home run hitting, and incredibly, he also now holds the record for career home run percentage over the legendary Babe Ruth.

Both Ruth and Gibson were the whole package when it came to playing the game. Ruth was also a great pitcher who could throw as well as he could hit, while Gibson was a star catcher. Gibson’s numbers don’t lie, and the argument can be made that he is the greatest ballplayer to ever swing a bat, although it is the nature of baseball fans that this will be debated until the end of time.

Still, this is stunning news that completely rewrites the history of baseball, and corrects an unjust policy that prevented black players from playing with MLB teams. Instead, those highly skilled players were segregated to the Negro Leagues until Jackie Robinson famously smashed the ‘color barrier’ when he donned his cleats and stepped onto Ebbets Field on April 15, 1947 for his first game with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Tragically, Gibson died of a stroke just months earlier, and so never lived to see a black man play in the majors. For that, and for so many other reasons, Gibson perhaps personifies better than any other person the struggle that Negro League players and their families have gone through, just to be recognized for their accomplishments.

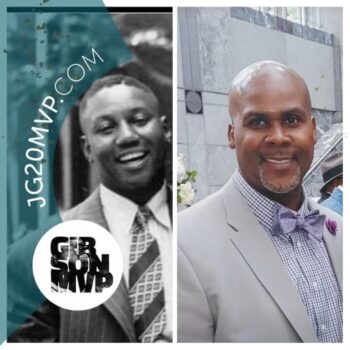

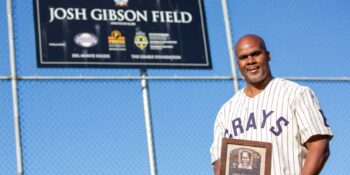

Sean Gibson, the great grandson of the famed power hitter, and CEO of the Josh Gibson Foundation, is one of the many people who have been fighting for this recognition.

“I will never forget that day,” Gibson told me. “May 29, 2024 is the day the MLB officially announced they would include and integrate the Negro League stats into the Major League Baseball record books. It was not just a great day for the Gibson family, but for all the families of Negro League players who have been denied this recognition for so long.”

Those stats will officially be entered into the MLB record books this week, but there are other types of recognition that the Negro League players have earned, and one of those involves the licensing industry. White players even in those early years of the MLB won fame, fortune and lucrative marketing or licensing deals, but there are no trading cards, Nike shoes, or apparel deals for members of the Negro Leagues.

That is something that will certainly change, and it’s about time.

Gibson works with the families of Negro League players, and says that after all the decades when they were denied recognition, licensees are now reaching out to discuss licensing deals for Josh Gibson.

“Topps has reached out to us, Panini reached out to us about doing baseball cards, and we’re looking at doing some merchandising deals with Dick’s Sporting Goods, which to me makes a lot of sense, because they are headquartered right here in Pittsburgh where Josh played,” Gibson says. “Now that this has happened and it’s official, we want to do some bigger things, like getting a sponsor to do billboards about the stats, maybe getting some commercials going about it, or negotiating some book deals.

“We’d also love to do a movie on Josh Gibson, and I think Josh has a really great story to tell.”

He certainly does. Gibson’s life was filled with both triumph and tragedy. He overcame great adversity while putting up some of the best stats of any athlete in the history of baseball, but he also lived with the frustration and injustice that his accomplishments weren’t being recognized by the wider baseball world.

Gibson was born in Georgia in 1911, and moved to Pennsylvania when his father got a job working in coal mines. He got his break when the player Buck Ewing was injured in 1930, and in a very short time he was blowing the minds of coaches and players for both his abilities as a catcher and his incredible power at the plate.

Hooks Tinker, the last surviving Grays player, said before his death in 2000 that the 220-pound Gray “was built like sheet metal. If you ran into him, it was like you ran into a wall.” And while this story can’t be verified, Grays teammate Buck Leonard once said he’d pesonally seen Gibson smash a ball 600 feet at Manhattan’s Polo Grounds.

But while he excelled on the field, Gibson faced tragedy at home, particularly when his wife died during leaving him a widower with children and facing the possible end of his baseball career.

“He was 18 when he married and his wife died at 17 giving birth to the twins,” Sean Gibson explains. “He had to make a big decision to either stay home and raise a family or continue his baseball career, and he was blessed that his in-laws raised the twins while he continued his baseball career, and thanks to them, the rest is history.”

Gibson soon became the best paid player in the Negro Leagues, supporting his family with the $6,000 he earned every season, as well as another $3,000 he earned over the winter playing in Latin America, which was good money considering the average wage for a man in 1940 was under $1,000 a year.

Tragically, however, Gibson was diagnosed with cancer in his early 30s, and died of a stroke at the age of 35, just a few months before the first black players entered the majors.

Sean Gibson says that puts him in the same company as the thousands of other men who were denied a fair shot at playing in the MLB.

“I have heard people say that players in the Negro Leagues should not be in the record book for the MLB, but I say, you simply can’t talk about baseball without talking about the Negro League players,” Gibson says. “It is very much a part of our history, and these guys deserved to be right there with their counterparts in the MLB because, as everybody can now see, they were just as good and in some cases they were better.

“The other thing is that Josh is getting all the attention right now, of course, because he is now the record holder for a number of different stats, but this story isn’t just about Josh; it’s about the more than 2,300 men who were all denied the right to play in the major leagues.”

Gibson also says that’s why he and other families of the Negro League players would like to form licensing partnerships.

“Licensing is important, because in the world we live in, people express their support or their affiliation with a player through the merchandise they buy,” Gibson says. “It might be a trading card, or a T-shirt, or a pair of shoes, but whatever it is, sports memorabilia is a major way that fans engage with and remember their favorite players, and that’s what we want for Josh Gibson and the other greats of the Negro Leagues.”

Gibson has engaged the licensing lawyer Edward Schauder of the law firm Neason Yeager as the family’s agent. Schauder says he is already very active in discussions for licensing collaborations in a number of categories, but he adds that the defining feature of a partnership won’t be just about money.

“The family is entertaining all offers in all categories, from sneakers, apparel, trading cards to book deals, but they want to make sure those potential deals align with their values,” Schauder says. “We are looking for licensing opportunities for companies that want to associate with an all-time great that is consistent with the Josh Gibson brand and values.”

Those values include the Gibson family’s desire to help other disadvantaged athletes achieve their dreams.

“A portion of the proceeds from the licensing program benefits the Josh Gibson Foundation,” Schauder says. “We also want people to know that Gibson’s licensing rights are only available through Josh Gibson Enterprises,” which is an organization set up to manage the late player’s brand and intellectual property.

Sean Gibson says the idea of the foundation is to create the type of opportunities that were often denied to young black athletes when Josh Gibson grew up.

“The goal is to provide the type of access that Josh never enjoyed for the youth of the Pittsburgh community,” Gibson says. “The foundation is working to provide academic and athletic programs that could allow the next Josh Gibson to reach his or her potential.”

As well, Gibson says the foundation hopes to establish The Josh Gibson Negro League Museum in Pittsburgh, to tell the story of the Negro Leagues. The Foundation and many other people are also trying to convince the MLB that it should name the annual Most Valuable Player award after Josh Gibson.

Originally the MVP award was named after Kennesaw Mountain Landis, who was the first commissioner of baseball for the MLB, but he was also the man who set the policy that banned black players from the league, resulting in the organization of the segregated Negro Leagues.

“He was the one who denied all those guys, including Josh, the opportunity to play in the majors,” Gibson says. “I think there’s a certain ironic justice in replacing him with Josh Gibson, as he’s the one who kept arguably the best player in baseball history out of the MLB!” To push that idea forward, Gibson and the Negro League families have set up a petition at jg20mvp.com.

Gibson also works with the Negro League Family Alliance, a group of family members who work on getting recognition for the players, and the Negro League Baseball Players Association, which was set up by Schauder and some partners. Those groups are currently lobbying to establish a National Negro League Day on May 2 every year, as that was the day in 1920 when the first Negro Leagues game was played.

“I co-founded the Negro League Baseball Players Association in April 1990 with a goal of educating the public of how great African American players were, but who were not allowed to play MLB, Schauder says. “Josh Gibson Jr. was a close friend and he was quoted in the New York Times in September 1991 as saying, ‘We want to be remembered as more than just a footnote to what the big leaguers did.’

“Josh was a tremendous athlete who deserved the right to compete with Major Leaguers,” Schauder adds. “He was precluded from doing so. He died very young at the age of 35 which is tragic. Now, Josh Gibson is a GOAT (Greatest Of All Time) sitting at the top of MLB’s stories records. The public needs to understand how great Josh and the other Negro Leaguers were, so my job is to help educate the public though the licenses we convey and make sure that Josh Gibson gets fair value as an all-time great and is not exploited.”

Now the MLB has announced the inclusion of the Negro Leagues records, Schauder says licensees are very keen to learn about the story and get involved.

“We’ve had numerous calls for trading cards, apparel, bubbleheads and memorabilia,” he says. “I have also been aggressive approaching potential licensees for the types of deals and brands that any GOAT, like Josh Gibson, should be associated with.

“I want to see the Gibson brand elevated to icon status,” Schauder adds. “Billboards with Josh Gibson’s likeness for brands that conveys integrity, greatness, perseverance and grace. Commercials like the famous Mean Joe Greene commercial where Josh Gibson is about to play ball in a major League Stadium and a young white baseball fan gives Josh a Coca Cola.

“Basically, I want to see Josh Gibson and all the other players finally get the recognition they should have gotten so many years ago.”